Smartphones vs Tablets: Does size matter?

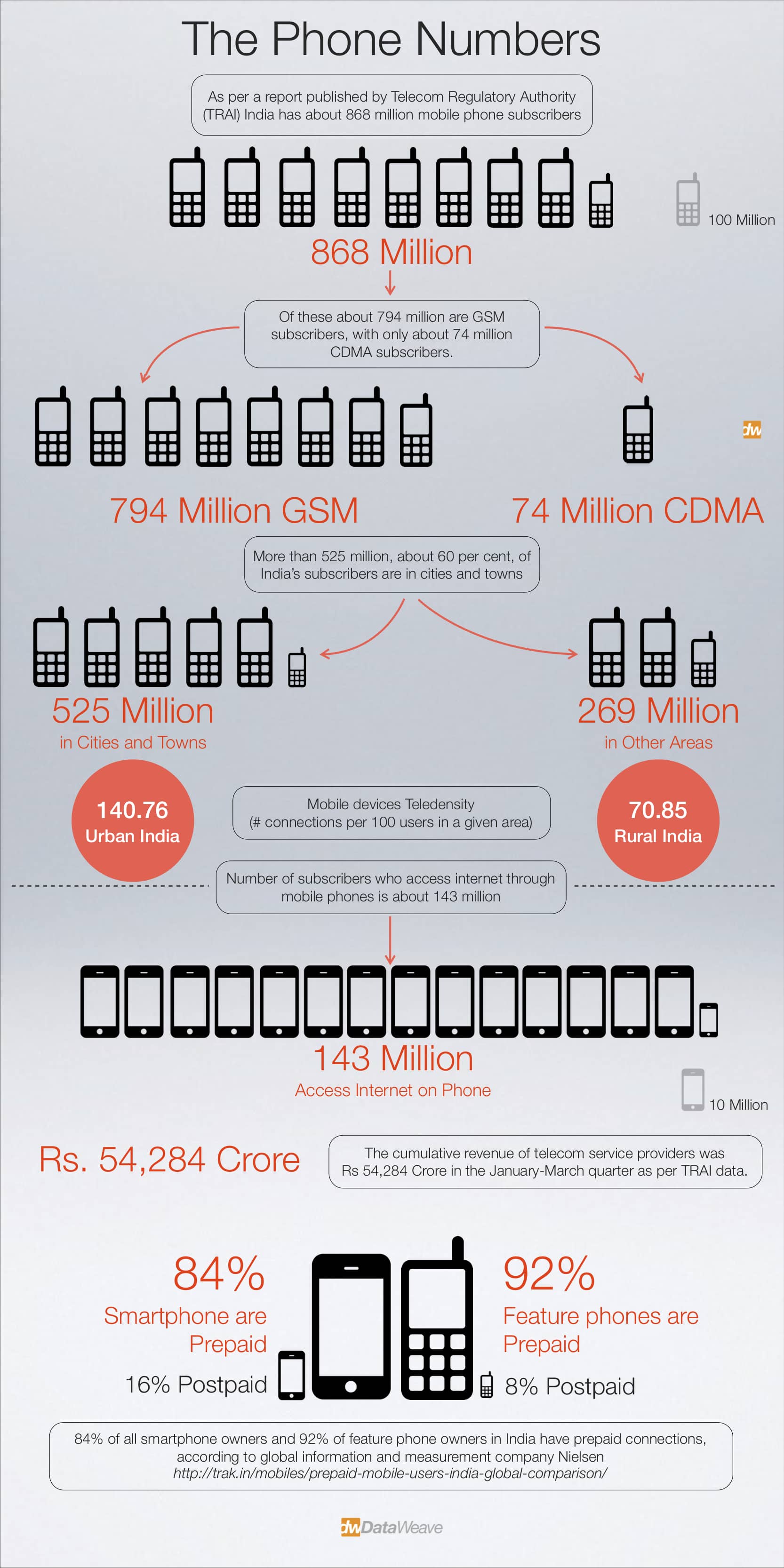

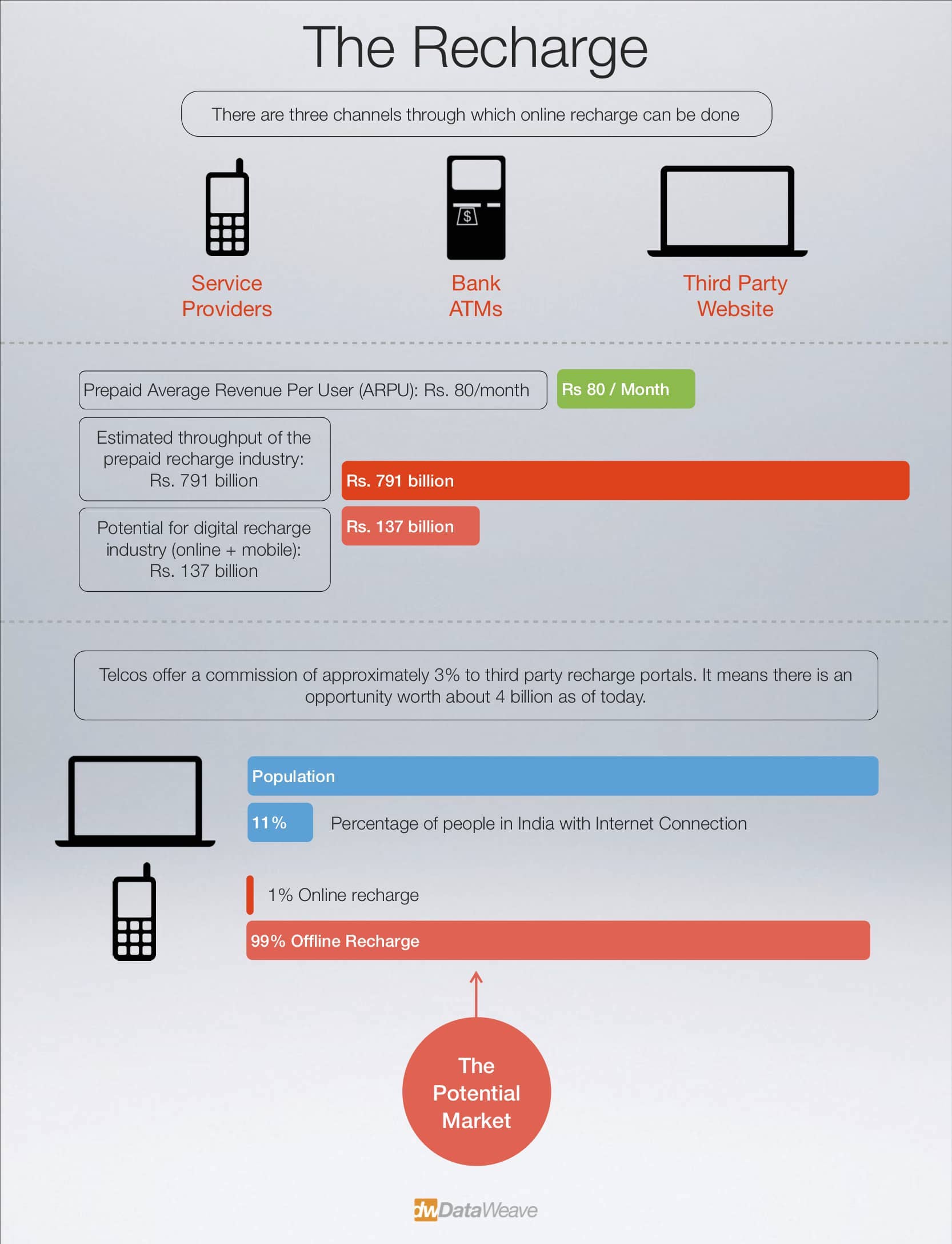

We have seen a steady increase in the number of smartphones and tablets since the last five years. Looking at the number of smartphones, tablets and now wearables ( smart watches and fitbits ) that are being launched in the mobiles market, we can truly call this ‘The Mobile Age’.

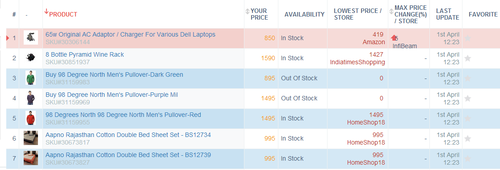

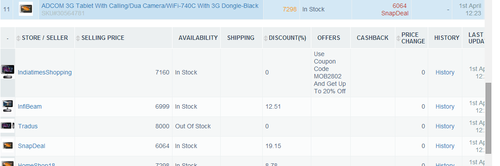

We, at DataWeave, deal with millions of data points related to products which vary from electronics to apparel. One of the main challenges we encounter while dealing with this data is the amount of noise and variation present for the same products across different stores.

One particular problem we have been facing recently is detecting whether a particular product is a mobile phone (smartphone) or a tablet. If it is mentioned explicitly somewhere in the product information or metadata, we can sit back and let our backend engines do the necessary work of classification and clustering. Unfortunately, with the data we extract and aggregate from the Web, chances of finding this ontological information is quite slim.

To address the above problem, we decided to take two approaches.

- Try to extract this information from the product metadata

- Try to get a list of smartphones and tablets from well known sites and use this information to augment the training of our backend engine

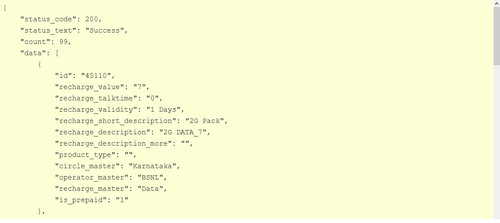

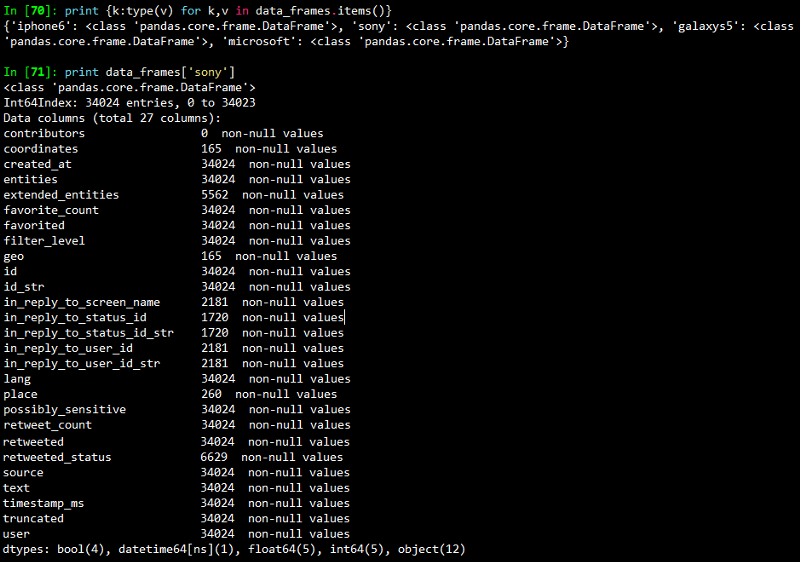

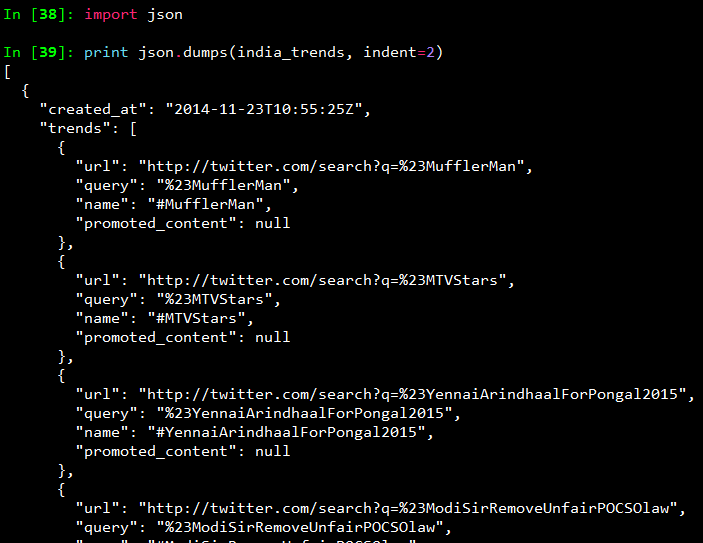

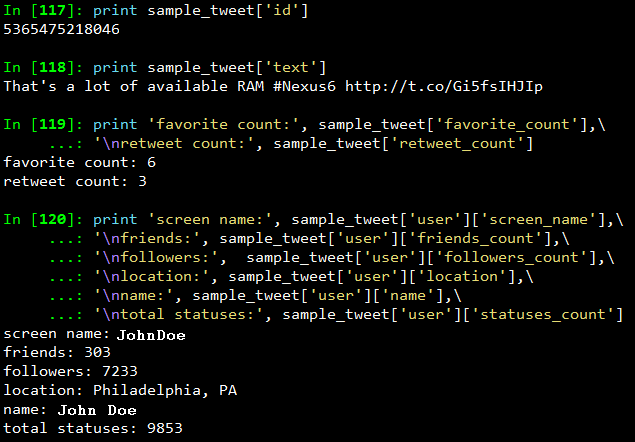

Here we will talk mainly about the second approach since it is more challenging and engaging than the former. To start with, we needed some data specific to phone models, brands, sizes, dimensions, resolutions and everything else related to the device specifications. For this, we relied on a popular mobiles/tablets product information aggregation site. We crawled, extracted and aggregated this information and stored it as a JSON dump. Each device is represented as a JSON document like the sample shown below.

{ "Body": { "Dimensions": "200 x 114 x 8.7 mm", "Weight": "290 g (Wi-Fi), 299 g (LTE)" }, "Sound": { "3.5mm jack ": "Yes", "Alert types": "N/A", "Loudspeaker ": "Yes, with stereo speakers" }, "Tests": { "Audio quality": "Noise -92.2dB / Crosstalk -92.3dB" }, "Features": { "Java": "No", "OS": "Android OS, v4.3 (Jelly Bean), upgradable to v4.4.2 (KitKat)", "Chipset": "Qualcomm Snapdragon S4Pro", "Colors": "Black", "Radio": "No", "GPU": "Adreno 320", "Messaging": "Email, Push Email, IM, RSS", "Sensors": "Accelerometer, gyro, proximity, compass", "Browser": "HTML5", "Features_extra detail": "- Wireless charging- Google Wallet- SNS integration- MP4/H.264 player- MP3/WAV/eAAC+/WMA player- Organizer- Image/video editor- Document viewer- Google Search, Maps, Gmail,YouTube, Calendar, Google Talk, Picasa- Voice memo- Predictive text input (Swype)", "CPU": "Quad-core 1.5 GHz Krait", "GPS": "Yes, with A-GPS support" }, "title": "Google Nexus 7 (2013)", "brand": "Asus", "General": { "Status": "Available. Released 2013, July", "2G Network": "GSM 850 / 900 / 1800 / 1900 - all versions", "3G Network": "HSDPA 850 / 900 / 1700 / 1900 / 2100 ", "4G Network": "LTE 800 / 850 / 1700 / 1800 / 1900 / 2100 / 2600 ", "Announced": "2013, July", "General_extra detail": "LTE 700 / 750 / 850 / 1700 / 1800 / 1900 / 2100", "SIM": "Micro-SIM" }, "Battery": { "Talk time": "Up to 9 h (multimedia)", "Battery_extra detail": "Non-removable Li-Ion 3950 mAh battery" }, "Camera": { "Video": "Yes, 1080p@30fps", "Primary": "5 MP, 2592 x 1944 pixels, autofocus", "Features": "Geo-tagging, touch focus, face detection", "Secondary": "Yes, 1.2 MP" }, "Memory": { "Internal": "16/32 GB, 2 GB RAM", "Card slot": "No" }, "Data": { "GPRS": "Yes", "NFC": "Yes", "USB": "Yes, microUSB (SlimPort) v2.0", "Bluetooth": "Yes, v4.0 with A2DP, LE", "EDGE": "Yes", "WLAN": "Wi-Fi 802.11 a/b/g/n, dual-band", "Speed": "HSPA+, LTE" }, "Display": { "Multitouch": "Yes, up to 10 fingers", "Protection": "Corning Gorilla Glass", "Type": "LED-backlit IPS LCD capacitive touchscreen, 16M colors", "Size": "1200 x 1920 pixels, 7.0 inches (~323 ppi pixel density)" } }

From the above document, it is clear that there are a lot of attributes that can be assigned to a mobile device. However, we would not need all of them for building our simple algorithm for labeling smartphones and tablets. I had decided to use the device screen size for separating out smartphones vs tablets, but I decided to take some suggestions from our team. After sitting down and taking a long, hard look at our dataset, Mandar had an idea of using the device dimensions also for achieving the same goal!

Finally, the attributes that we decided to use were,

- Size

- Title

- Brand

- Device dimensions

Screen sizeI wrote some regular expressions for extracting out the features related to the device screen size and resolution. Getting the resolution was easy, which was achieved with the following Python code snippet. There were a couple of NA values but we didn’t go out of our way to get the data by searching on the web because resolution varies a lot and is not a key attribute for determining if a device is a phone or a tablet.

size_str = repr(doc["Display"]["Size"]) resolution_pattern = re.compile(r'(?:\S+\s)x\s(?:\S+\s)\s?pixels') if resolution_pattern.findall(size_str): resolution = ''.join([token.replace("'","") for token in resolution_pattern.findall(size_str)[0].split()[0:3]]) else: resolution = 'NA'

But the real problems started when I wrote regular expressions for extracting the screen size. I started off with analyzing the dataset and it seemed that screen size was mentioned in inches so I wrote the following regular expression for getting screen size.

size_str = repr(doc[“Display”][“Size”]) screen_size_pattern = re.compile(r'(?:\S+\s)\s?inches’) if screen_size_pattern.findall(size_str): screen_size = screen_size_pattern.findall(size_str)[0].split()[0] else: screen_size = ‘NA’

However, I noticed that I was getting a lot of ‘NA’ values for many devices. On looking up the same devices online, I noticed there were three distinct patterns with regards to screen size. They are,

- Screen size in ‘inches’

- Screen size in ‘lines’

- Screen size in ‘chars’ or ‘characters’

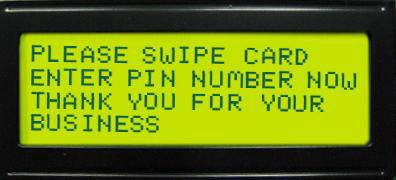

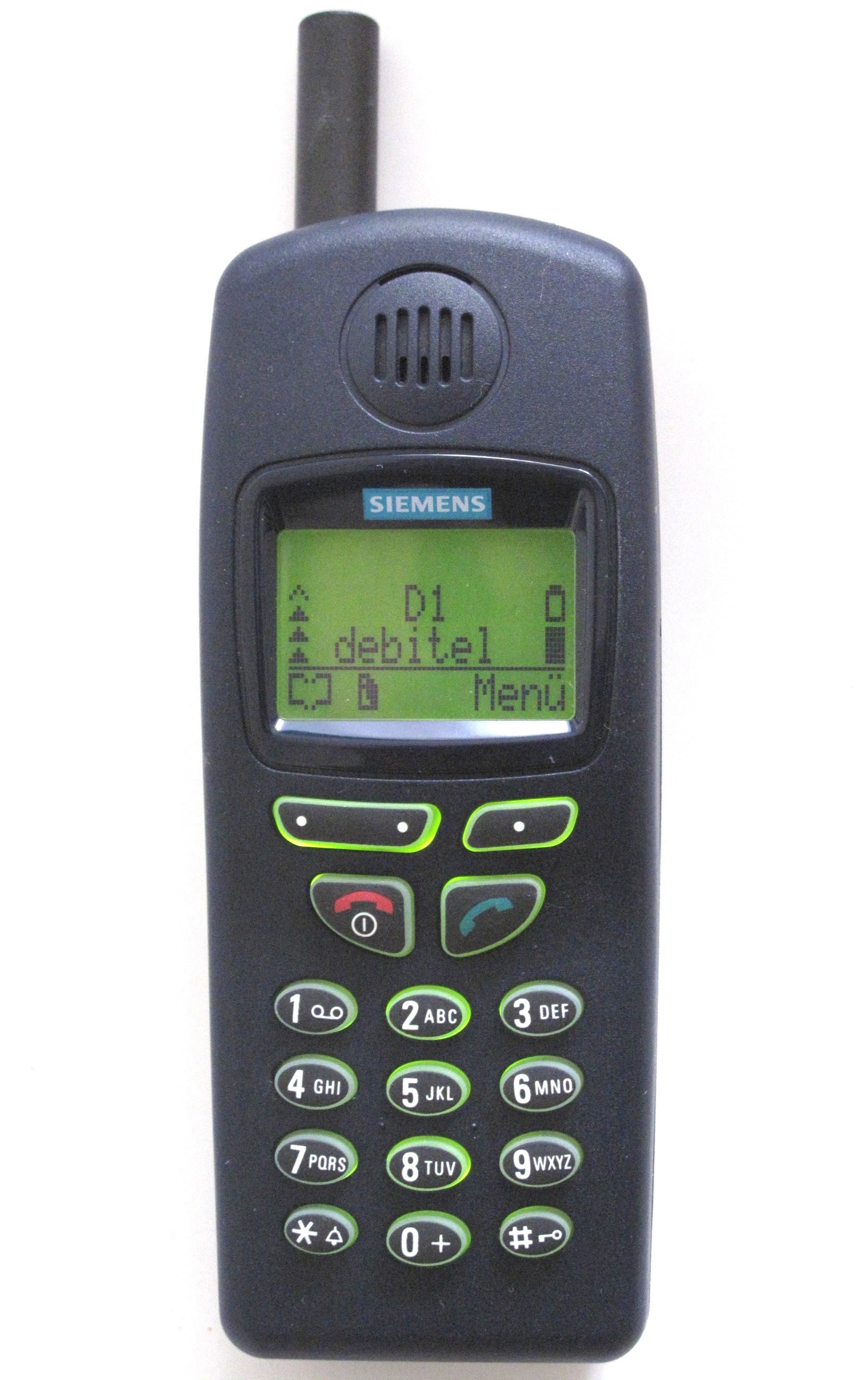

Now, some of you might be wondering what on earth do ‘lines’ and ‘chars’ mean and how do they measure screen size. On digging it up, I found that basically both of them mean the same thing but in different formats. If we have ‘n lines’ as the screen size, it means, the screen can display at most ‘n’ lines of text at any instance of time. Likewise, if we have ‘n x m chars’ as the screen size, it means the device can diaplay ‘n’ lines of text at any instance of time with each line having a maximum of ‘m’ characters. The picture below will make things more clear. It represents a screen of 4 lines or 4 x 20 chars.

Thus, the earlier logic for extracting screen size had to be modified and we used the following code snippet. We had to take care of multiple cases in our regexes, because the data did not have a consistent format.

Thus, the earlier logic for extracting screen size had to be modified and we used the following code snippet. We had to take care of multiple cases in our regexes, because the data did not have a consistent format.

size_str = repr(doc["Display"]["Size"]) screen_size_pattern = re.compile(r'(?:\S+\s)\s?inc[h|hes]') if screen_size_pattern.findall(size_str): screen_size = screen_size_pattern.findall(size_str)[0] .replace("'","").split()[0]+' inches' else: screen_size_pattern = re.compile(r'(?:\S+\s)\s?lines') if screen_size_pattern.findall(size_str): screen_size = screen_size_pattern.findall(size_str)[0] .replace("'","").split()[0]+' lines' else: screen_size_pattern = re.compile(r'(?:\S+\s)x\s(?:\S+\s)\s?char[s|acters]') if screen_size_pattern.findall(size_str): screen_size = screen_size_pattern.findall(size_str)[0] .replace("'","").split()[0]+' lines' else: screen_size = 'NA'

Mandar helped me out with extracting the ‘dimensions’ attribute from the dataset and performing some transformations on it to get the total volume of the phone. It was achieved using the following code snippet.

dimensions = doc['Body']['Dimensions'] dimensions = re.sub (r'[^\s*\w*.-]', '', dimensions.split ('(') [0].split (',') [0].split ('mm') [0]).strip ('-').strip ('x') if not dimensions: dimensions = 'NA' total_area = 'NA' else: if 'cc' in dimensions: total_area = dimensions.split ('cc') [0] else: total_area = reduce (operator.mul, [float (float (elem.split ('-') [0])/10) for elem in dimensions.split ('x')], 1) total_area = round(float(total_area),3)

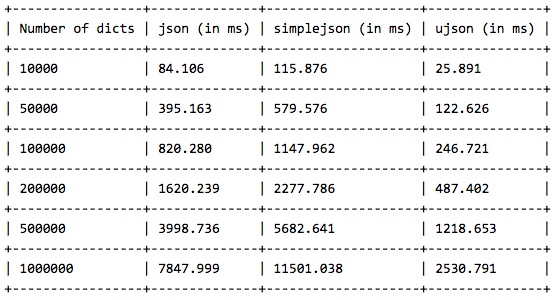

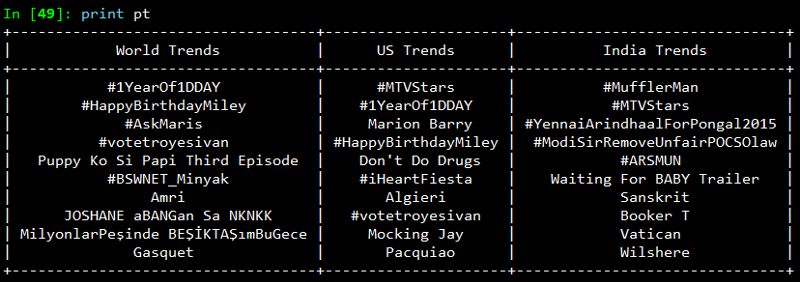

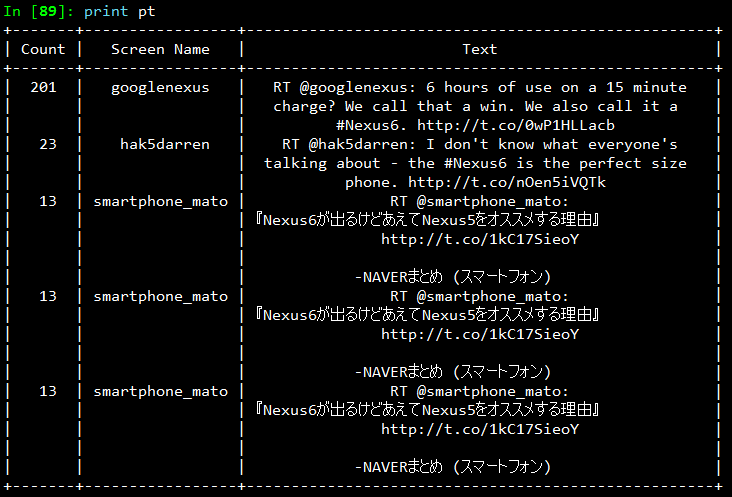

We used PrettyTable to output the results in a clear and concise format.

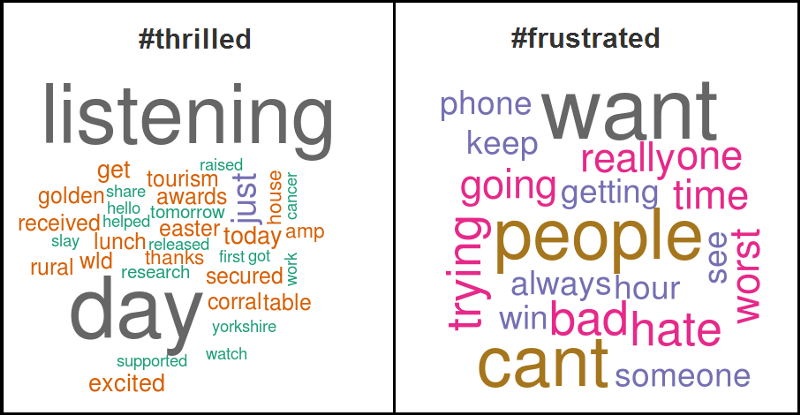

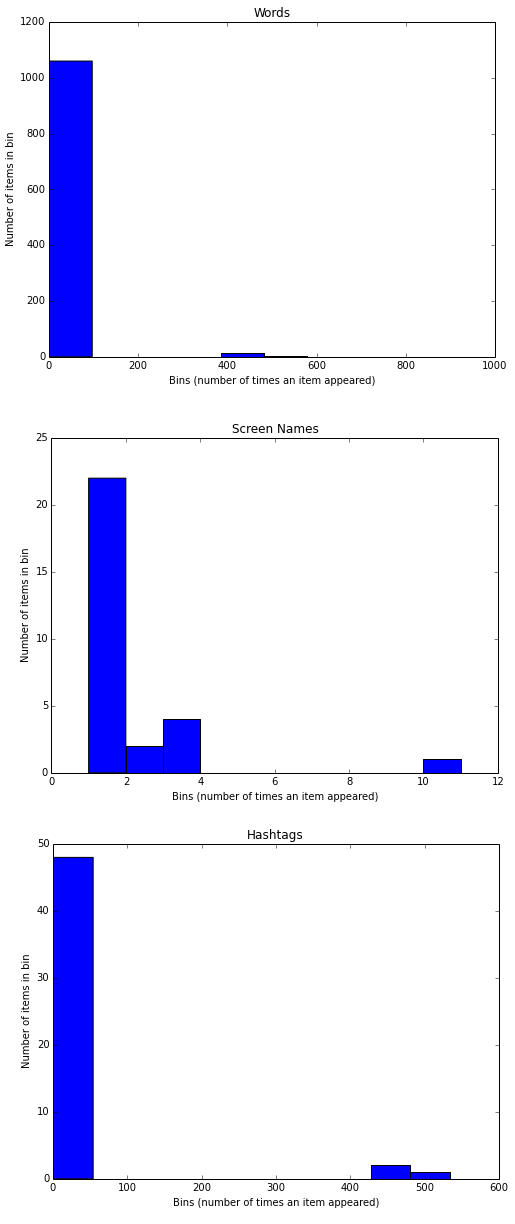

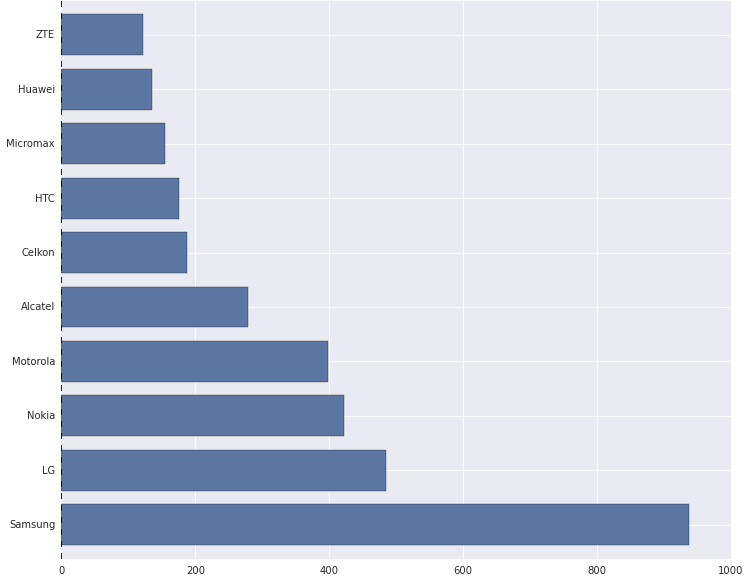

Next, we stored the above data in a csv file and used Pandas, Matplotlib, Seaborn and IPython to do some quick exploratory data analysis and visualizations. The following depicts the top ten brands with the most number of mobile devices as per the dataset.

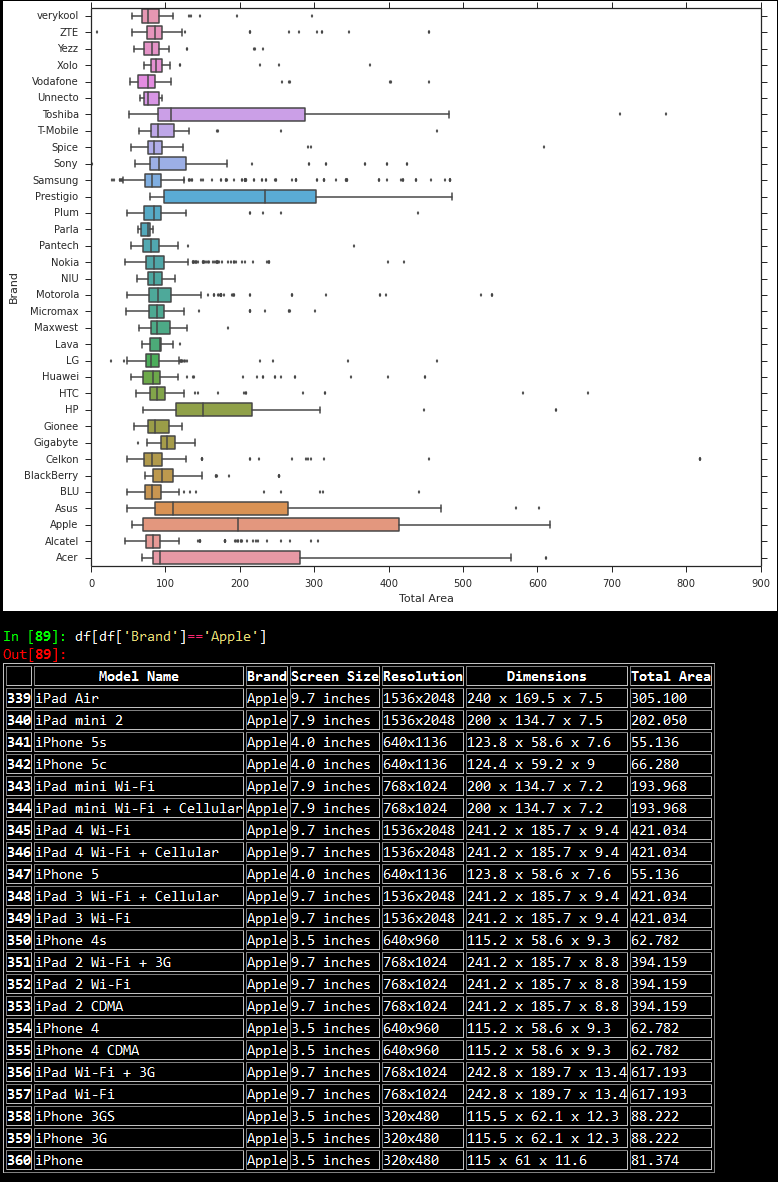

Then, we looked at the device area frequency for each brand using boxplots as depicted below. Based on the plot, it is quite evident that almost all the plots are right skewed, with a majority of the distribution of device dimensions (total area) falling in the range [0,150]. There are some notable exceptions like ‘Apple’ where the skew is considerably less than the general trend. On slicing the data for the brand ‘Apple’, we noticed that this was because devices from ‘Apple’ have an almost equal distribution based on the number of smartphones and tablets, leading to the distribution being almost normal.

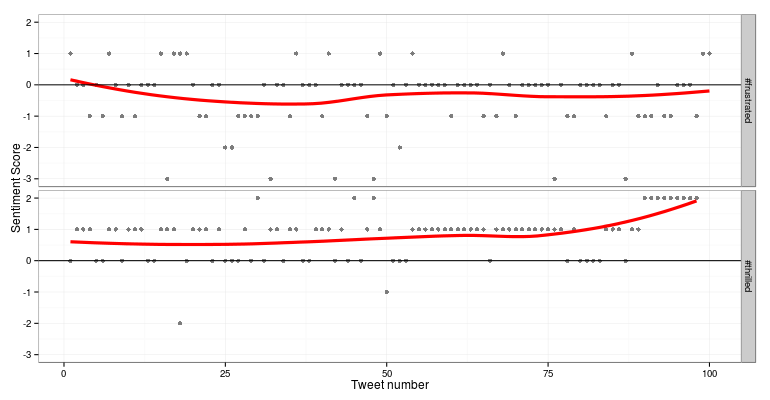

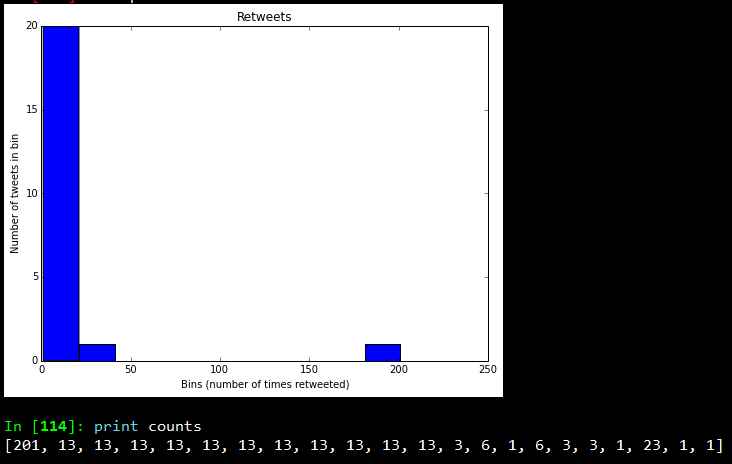

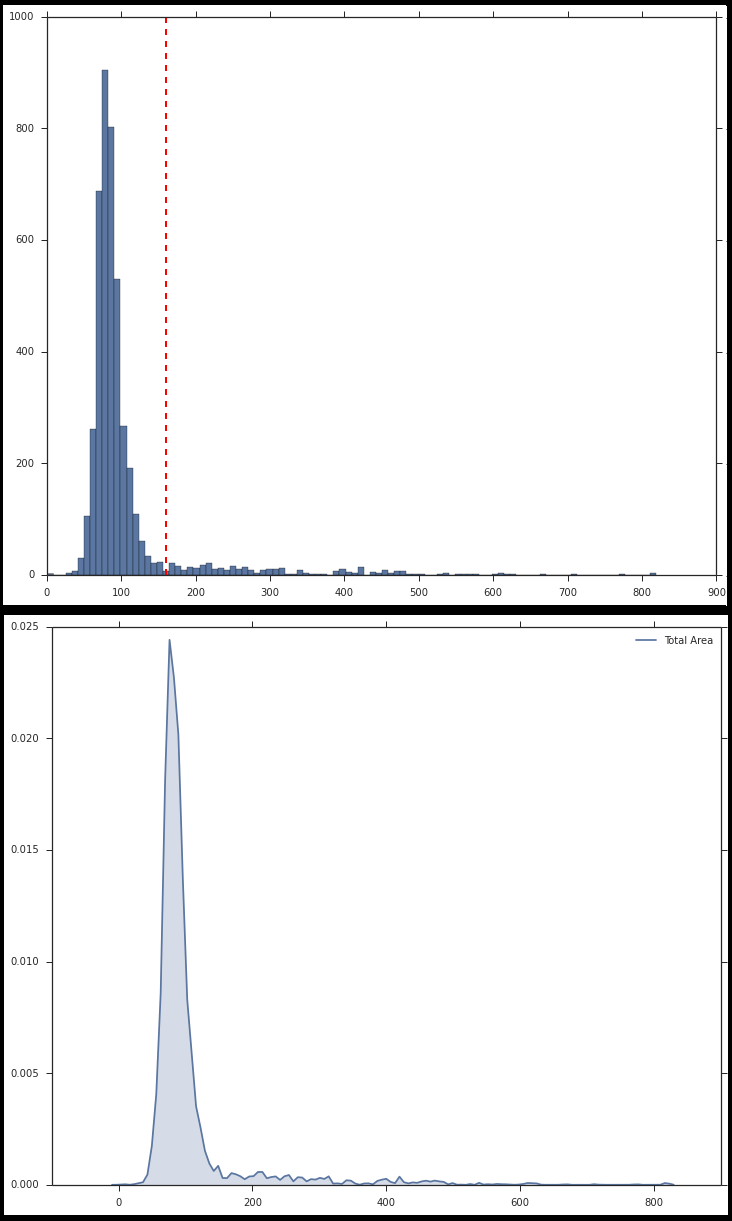

Based on similar experiments, we noticed that tablets had larger dimensions as compared to mobile phones, and screen sizes followed that same trend. We made some quick plots with respect to the device areas as shown below.

Now, take a look at the above plots again. The second plot shows the distribution of device areas in a kernel density plot. This distribution resembles a Gaussian distribution but with a right skew. [Mandar reckons that it actually resembles a Logistic distribution, but who’s splitting hairs, eh? ;)] The histogram plot depicts the same, except here we see the frequency of devices vs the device areas. Looking at it closely, Mandar said that the bell shaped curve had the maximum number of devices and those must be all the smartphones, while the long thin tail on the right side must indicate tablets. So we set a cutoff of 160 cubic centimeters for distinguishing between phones and tablets.

We also decided to calculate the correlation between ‘Total Area’ and ‘Screen Size’ because as one might guess, devices with larger area have large screen sizes. So we transformed the screen sizes from textual to numeric format based on some processing, and calculated the correlation between them which came to be around 0.73 or 73%

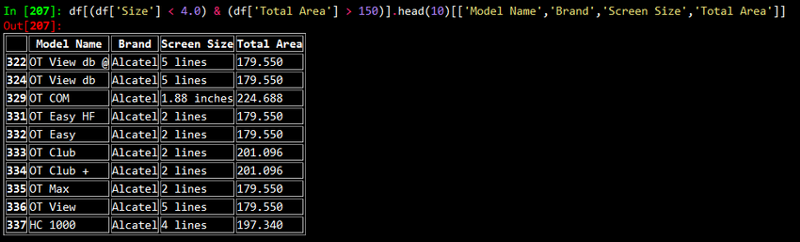

We did get a high correlation between Screen Size and Device Area. However, I still wanted to investigate why we didn’t get a score close to 90%. On doing some data digging, I noticed an interesting pattern.

After looking at the above results, what came to our minds immediately was: why do phones with such small screen sizes have such big dimensions? We soon realized that these devices were either “feature phones” of yore or smartphones with a physical keypad!

Thus, we used screen sizes in conjunction with dimensions for labeling our devices. After a long discussion, we decided to use the following logic for labeling smartphones and tablets.

device_class = None if total_area >= 160.0: device_class = 'Tablet' elif total_area < 160.0: device_class = 'Phone' if 'lines' in screen_size: device_class = 'Phone' elif 'inches' in screen_size: if float(screen_size.split()[0]) < 6.0: device_class = 'Phone'

After all this fun and frolic with data analysis, we were able to label handheld devices correctly, just like we wanted it!

Originally published at blog.priceweave.com.